Kitsiksíksimatsimmo!

The Story of 49 Design

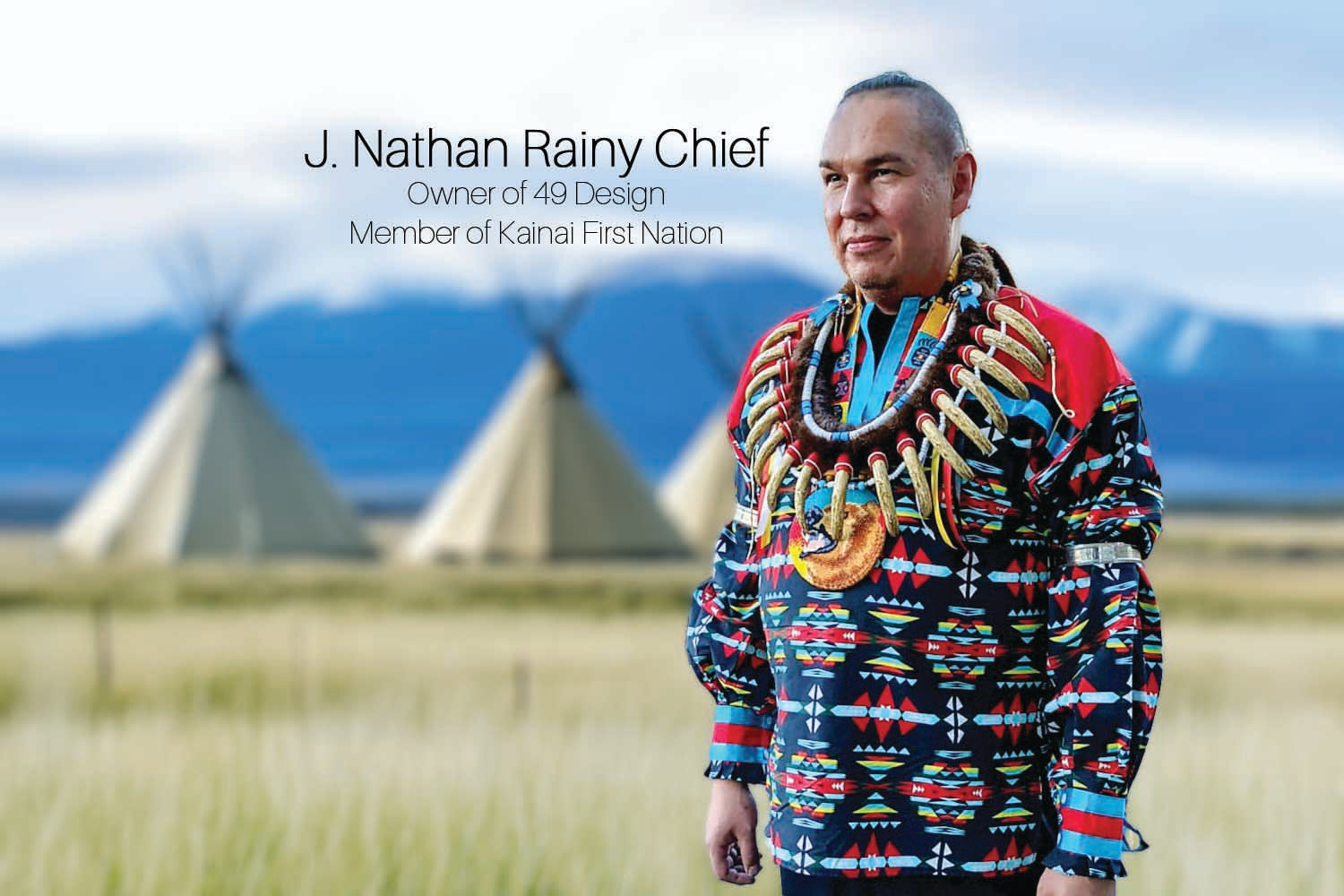

About Me

The stories of my family are not simply told—they are inherited, breathed into existence through generations of remarkable individuals. At the heart of these stories stands my great grandmother Margaret, a beacon of strength whose roots run deep into the rich soil of Niitsitapi history.

Her father, Charlie Davis, was a man born of profound legacy. Grandson of Rainy Chief—the legendary signatory of Treaty 7—and son of Falling Over A Bank, Charlie carried within him the complex history of a people constantly reimagining survival. Her mother, Rosie Davis, was equally remarkable—granddaughter of Chief Iron Pipe, daughter of Double Gun Woman, and a pivotal figure in the Matokiks Women's Society.

Margaret's kitchen was more than a room—it was an archive of memory, a sacred space where history whispered through every conversation. As a child, I would sit and listen, my ears catching the nuanced stories that seemed to float between remembrance and resilience. She would talk about her parents, about the profound transformations her family had witnessed, about the delicate art of adaptation that had kept our people strong.

Rosie, my great-great-grandmother, was the first in their family to attend an Indian Residential School—a journey that was neither simple nor straightforward. She carried with her the strength of Double Gun Woman, navigating institutions designed to erase her very existence. Yet she emerged, like so many Indigenous women, not broken, but transformed.

Charlie Davis inherited the leadership of his father Falling Over A Bank and grandfather Rainy Chief—not just as a title, but as a profound responsibility. He understood that leadership was about more than authority; it was about preserving culture, protecting community, and finding ways to thrive in a world that constantly sought to diminish Indigenous possibility.

These stories became my inheritance. As a Two-Spirit, autistic individual, I recognized in my family's history a similar pattern of survival—of finding strength in spaces never intended for us, of transforming limitation into opportunity.

My great grandmother Margaret would laugh her big, revolutionary laugh—a sound that contained entire histories. She taught me that our stories are not defined by the challenges we face, but by our extraordinary capacity to reimagine ourselves. Each generation carries forward the wisdom of those who came before, weaving a continuous thread of resilience.

In my own entrepreneurial journey, I am not just building a business. I am continuing a legacy of transformation, of creating pathways where none existed. The same spirit that allowed Rainy Chief to negotiate Treaty 7, that enabled Rosie to survive the residential school system, that saw Charlie Davis lead with diplomacy—this spirit lives in me.

Our history is not a static collection of dates and names. It is a living, breathing narrative of survival, of profound adaptability. And in every decision I make, in every challenge I overcome, I hear the whispers of my ancestors—guiding, encouraging, reminding me of the extraordinary strength that flows through my veins.

About the Company

The absence was profound. Growing up, I noticed the void where Indigenous creativity should have lived—our vibrant, intricate designs missing from television screens, magazine spreads, the very fabric of everyday life. This erasure was more than visual. It was a continued attempt to minimize the extraordinary complexity of Indigenous artistic expression.

My grandmothers were extraordinary beadworkers. Their hands moved like storytellers, crafting pieces central to our tribe's ceremonial life. Each stitch was a conversation, each design a living narrative passed through careful, deliberate movements. They showed me that our art was never meant to be confined—it was meant to breathe, to expand, to transform.

49 Design emerged from this understanding—a vision to bring Indigenous design into everyday life through apparel, home goods, footwear, fabric, and beyond. We are not simply creating products. We are continuing a conversation that has existed for generations, reimagining how Indigenous creativity can exist in the world.

Our journey has taken us across North America—to powwows, gatherings, events, councils—mapping a different kind of landscape. Each travel was a cartography of possibility, exploring the vast territories of Indigenous design. We weren't just moving through space; we were tracing the invisible lines of cultural continuity.

Design, for us, is never just about lines and colors. It is a language of memory, a dialogue between tradition and innovation. Each collection begins with a story—sometimes a whispered memory from an elder, sometimes a fragment of a ceremonial tradition, sometimes a quiet moment of personal reflection.

We are not a manufacturing company in the traditional sense. With the exception of our handmade section—which features items we create in-house or that local Indigenous artisans craft—we are strictly a design company. But this is not a limitation. It is a deliberate act of creative sovereignty.

Commerce is not a betrayal of culture. It is another landscape of resilience, another pathway of survival. Our manufacturing partnerships are carefully considered collaborations, not disconnections from our cultural core. Each piece begins with a story, a memory, or a rite of passage that we translate into a unique design.

When people engage with our designs, they are not consuming a product. They are participating in a story—a story of survival, of beauty, of profound cultural continuity. Every collection we produce is a continuation of our narrative, blending tradition with innovation to celebrate Indigenous culture in every detail.

Our entrepreneurship is an act of love. Love for our cultures, for our stories, for the extraordinary resilience that has always defined Indigenous experience. We are not preserving culture in a static sense. We are proving that culture is alive, that it breathes, that it can wear itself proudly in the world—on bodies, in homes, across landscapes that once tried to erase us.

Each design is an act of resistance, each product a statement that Indigenous creativity cannot be contained or diminished. We challenge the narrative that Indigenous design is historical or static. We prove, with every collection, that our creativity is contemporary, innovative, and endlessly transformative.

In the end, 49 Design is more than a company. It is a living archive, a cultural dialogue, a continuous act of storytelling. We are not just creating designs. We are creating visibility, showing the world the extraordinary depth and complexity of Indigenous artistic expression.

Our story continues, one design at a time.

About our Team

Memory has a way of marking time through the people who share our spaces. In 2020, when we opened the doors to Rainy Chief Trading Post—our flagship store named for an ancestor who signed Treaty 7—the morning light caught more than just displays. It illuminated the faces of our team, each person carrying stories that echo through generations.

Our predominantly Indigenous team moves through these spaces with an understanding that transcends retail experience. They carry within them histories of grandmothers who beaded late into the night, of aunties who taught them to recognize beauty in the smallest details, of ancestors who understood that commerce and culture were never meant to be separated.

When we expanded to Edmonton in 2021, opening our second 49 Design location, we weren't just growing a business. We were creating new territories of possibility, guided by individuals who understand intimately the responsibility of representing Indigenous creativity in contemporary spaces. Each carefully curated display represents hours of thoughtful collaboration, of stories shared across design tables, of dreams transformed into tangible reality.

The 49 Design Academy emerged from our team's collective understanding that our responsibility extends beyond commerce. In both locations, our instructors—artists and knowledge keepers in their own right—guide students through the intricate processes of traditional crafting. Watch their hands guide others through the gentle rhythm of beadwork or the careful measurements of a ribbon skirt, and you'll understand that we're doing more than teaching craft. We're facilitating the transmission of cultural knowledge.

Some of our team members carry the weight of residential school histories in their families. Others are first-generation entrepreneurs, breaking new ground while holding tight to ancestral teachings. Together, they create an atmosphere where Indigenous creativity flourishes naturally, where every interaction becomes an opportunity for cultural exchange and understanding.

In the quiet moments before opening, when sunlight streams through windows and catches the displays just so, I watch our team prepare for the day. Two dedicated individuals manage our wholesale division, building relationships that extend far beyond business. Four others navigate the digital realm with the same careful attention our ancestors gave to maintaining connections between communities. They are the sentinels of the E-commerce Made to Order site. Each person contributes their unique perspective to our collective vision. Our store-level teams interface with our fans and customers, building bridges and sharing the warmth of community that our people have always been known for.

The retail spaces showcase products that emerge from deep cultural understanding and meticulous attention to detail. Our team approaches curation not as a task, but as a ceremony—each piece selected with intention, each display arranged to tell stories that span generations. We're not just filling shelves; we're filling historical voids, creating presence where there was once absence.

These spaces hold more than inventory. They hold the collective dreams and determination of a team that understands the profound importance of Indigenous representation in contemporary design. Every student who learns to make their first ribbon skirt, every entrepreneur who discovers new ways to express cultural creativity through commerce, every curious visitor who engages with Indigenous design—they become part of our expanding story.

In the gentle hum of daily operations, our team moves with purpose and pride. They are knowledge keepers, story carriers, dream weavers working to ensure that Indigenous creativity continues to thrive in a world that once tried to silence it. Each morning, as they prepare to open our doors, they carry forward the teachings of those who came before us, imagining and building futures where Indigenous design speaks freely, proudly, and without constraint.

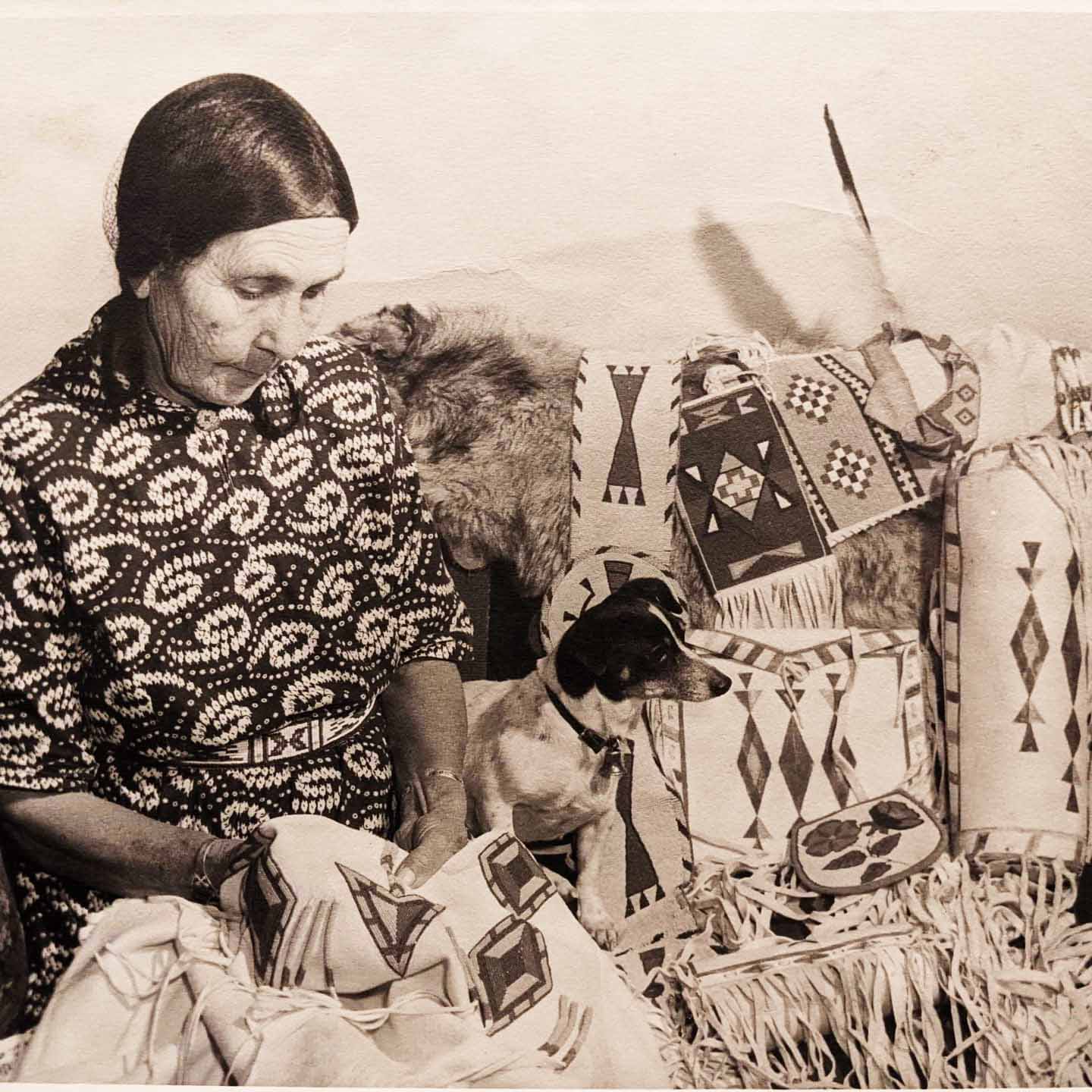

Rosie was an award-winning beadwork artist, and also made many traditional crafts, including parfleche, quillwork, buckskin items, among many other things. She was often called on to make special items for visiting dignitaries to Kainai First Nation. Several of her pieces are in museums across North America.

My great-great grandparents were true movers and shakers in Alberta history. Here they are pictured with an honorary (non-Native) chief of our tribe, along with their granddaughters. Charlie was a staunch Blackfoot traditionalist, and Rosie was a Blackfoot woman who mastered walking in both worlds as a translator for the RCMP, avid beadworker, knowledge keeper, and head of the women's society. Both Charlie and Rosie were the children of Trading Post owners and managers at Fort Whoop Up and Fort Macleod, respectively. They are both also descendants of prominent Blackfoot chiefs.

Double Gun Woman (aka Mary Iron Pipe) was the daughter of Chief Iron Pipe, and the mother of Rosie Davis. Here, she and her second husband, Joe Healy (aka Wolf Moccasin), are posed with their children in Lethbridge, AB near Fort Whoop Up. Joe Healy was an interpreter for Head Chief Red Crow, and was one of the only Blackfoot men of his age group who spoke English. Joe and Double Gun Woman went on to have a large family, which now includes over 3,000 descendants scattered across Canada, the United States, and other parts of the globe.